Religion. Morality. Knowledge. These are precepts to which Fr. Gabriel Richard lived throughout his entire life. He is a man not often read about in the Michigan history books, which is quite a shame, as he did much to help the early settlers in Michigan. Father Gabriel is also known by some as the second founder of Detroit. If a story were to be told about the early days of Michigan, he would be a leading character.

Gabriel Richard was born in LaVille de Saintes, France on October 15, 1767 to Francois and Marie Geneviver Richard. His family was close-knit and he grew up very sheltered from the political unrest that was building in France at the time. Gabriel was described as an energetic child who was given a good education.

At the age of 12 or 13, the always curious boy climbed the scaffolding of a chapel that was under construction. He fell and suffered serious injuries, one on his face which left a permanent scar. This event caused Gabriel to become a bit more serious and he settled into his studies. He was so successful in this endeavor that he considered attending the University of Paris, but his father had fallen on hard times and was unable to send him. Gabriel then decided to enter the seminary at Angers in October of 1784, which was a part of the Sulpician Society. He was a committed student and grew both academically and spiritually. During this time, he decided he would like to become a parish priest or a missionary.

The French Revolution was well on its way during this time period. Not only was the nobility in danger, but also the clergy. Many bishops and priests were arrested and imprisoned while some were even executed. Though his future was in doubt, Gabriel was ordained a priest and was sent to America almost immediately to protect him, though he was reportedly ready and willing to suffer martyrdom.

Fr. Gabriel Richard and three other immigrants arrived in Baltimore, Maryland on July 10, 1792. The men purchased a tavern outside the city and used it as classrooms. This would become St. Mary’s Seminary. Other priests joined the group, and it wasn’t long before Bishop John Carrol sent Fr. Gabriel west to minister to the settlers. His first assignment was in Kaskaskia, Illinois, and it was here that he met up with an old friend, Fr. Michael Levadoux. The two had great plans, and quickly built a new church and discussed the possibility of creating an academy that would expand into a seminary.

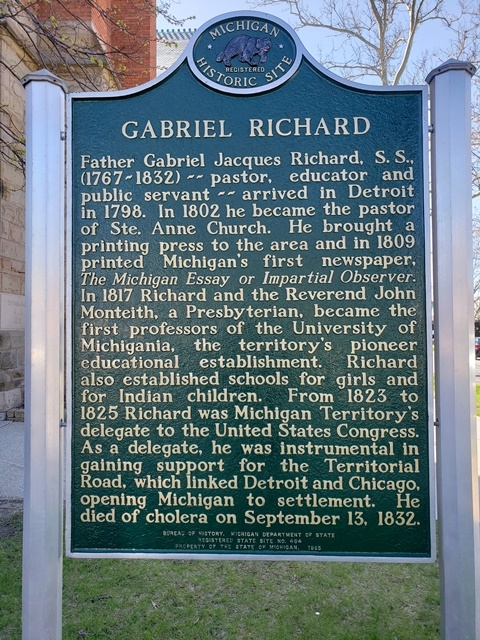

Fr. Gabriel worked hard at this post and continued to learn a lot. In 1793, Fr. Levadoux was sent to the new American territory in what is now Michigan. He quickly saw that the people needed a good spiritual leader, especially in the settlements of Mackinac, Detroit, River Rasin and Sault Ste. Marie. Fr. Levadoux requested help, and Fr. Gabriel was sent to the territory. He arrived on June 3, 1798.

Frs. Gabriel and Levadoux were in charge of the territory north of the Raisin River. They were determined to Americanize the northwest frontier, as they were developing a deep admiration for the growing United States. On June 20, 1799, Fr. Gabriel was sent to Mackinac. He sailed north and was understandably struck by the beauty of the straits. He spent two months teaching the Indian and American children Catechism, holding evening services, and giving instructions on Christian doctrine. He also visited St. Joseph’s Island and Sault Ste. Marie. He believed that the people of the northern settlements needed a permanent priest and many traders in the area tried persuading him to stay. However, Fr. Levadoux could not spare Fr. Gabriel in Detroit, as he felt his specific talents, such as speaking English as well as French, would be better served in that city.

Frs. Gabriel and Levadoux were in charge of the territory north of the Raisin River. They were determined to Americanize the northwest frontier, as they were developing a deep admiration for the growing United States. On June 20, 1799, Fr. Gabriel was sent to Mackinac. He sailed north and was understandably struck by the beauty of the straits. He spent two months teaching the Indian and American children Catechism, holding evening services, and giving instructions on Christian doctrine. He also visited St. Joseph’s Island and Sault Ste. Marie. He believed that the people of the northern settlements needed a permanent priest and many traders in the area tried persuading him to stay. However, Fr. Levadoux could not spare Fr. Gabriel in Detroit, as he felt his specific talents, such as speaking English as well as French, would be better served in that city.

Overseas, the French Revolution had ended, and French priests were being sent back to their homeland. Because of his now-failing health, Fr. Levadoux was sent back to Baltimore and eventually home to France. This left Fr. Gabriel with more duties in Detroit. His congregation was growing and he made significant efforts to renovate and enlarge St. Anne’s Church in Detroit. This rebuild took about two years.

As time passed, Fr. Gabriel wondered when he would be moved from Detroit or even sent back to France. However, on June 11, 1805, a fire tore through the settlement, destroying all of the buildings except for two. Fr. Gabriel went right to work, ministering to the people. This event solidified his resolve to remain in Southeast Michigan and help rebuild. It was at this time he said, “We hope for better things: it shall arise from the ashes.” To this day, his words are the motto of the city.

Fr. Gabriel traveled up and down the Detroit River, arranging lodging for the homeless and bringing food and blankets to those who needed them. He quickly took on a leadership position. For a while after the fire, Fr. Gabriel held services in a tent or the open air. Eventually, an old warehouse, one of the two buildings that escaped destruction in the fire, was refitted as the church and services were held there for the next three years.

Plans for a new church building dragged on for years, during which Fr. Gabriel spent some time in Washington and was even granted an audience with President Jefferson. When he returned to Michigan, he became a leader of civic activities as well as a spiritual leader. There was much work to do in the territory, politically and economically. Fr. Gabriel took it upon himself to educate the French in the area so they wouldn’t be taken advantage of by the Americans who would undoubtedly begin moving into the Michigan Territory. Tensions were high between these two groups, heightened by language barriers. Americans were suspicious of the loyalty of the French, and there was much distrust between them. Fr. Gabriel wanted to change this atmosphere. For example, before the fire, on April 20, 1805, he became a chaplain to the first regiment of the militia.

Fr. Gabriel went to Washington again in 1808 to present a petition to Congress. This petition was to help the farmers in the Detroit area. He later inspired a second petition asking Congress to have the laws of the territory be published in French as well as English, to help the French become familiar with American laws and customs.

Fr. Gabriel earned the respect and friendship of English-speaking Protestants in Detroit, which helped establish a better relationship between the Americans and French. He would even hold non-denominational religious services for those who did not have consistent church leadership. He also took a great interest in the relationship between the European settlers and the Indians, and did what he could to help both groups. He was especially concerned with the liquor trade and the government’s acquisition of Indian lands without just compensation.Fr. Gabriel traveled east again in 1808 and 1809. He brought back an organ and harpsichord, which excited the people of the city. He also arranged for a printing press to be brought to Detroit. On August 31, 1809, Detroit’s first hometown newspaper, The Michigan Essay, was released.

The year 1812 brought war to the United States, and the British and their Indian allies quickly moved on Detroit, capturing it on August 16, 1812. Fr. Gabriel and his followers remained as loyal as they could. When the British allowed the Indians to ransack the town, he spoke up at the risk of his own life. After the British victory at River Rasin, American prisoners were paraded through the streets of Detroit. Fr. Gabriel and other citizens raised money to ransom the men. The plan failed, and many leading citizens were exiled for their views. Surprisingly, Fr. Gabriel was allowed to stay. The British commander insisted that Fr. Gabriel take an oath of allegiance, but the priest refused. He was then placed under arrest and sent across the Detroit River. On June 16, 1813, he was given the opportunity of being released if he signed an agreement to keep his opinions to himself. Thinking of his congregation and the people of Detroit, he signed. One of the reasons the British commanders offered this agreement was at the insistence of the Indian chief, Tecumseh, who greatly admired Fr. Gabriel.

After the war, Fr. Gabriel worked to bring relief to the families that had been affected by the war. He worked with territorial governor, Lewis Cass to get federal aid to help the farmers in the area, then acted as the administrator of the relief. Americans and the French began working together to better the city of Detroit.

Though he did much for the general population of Detroit and eastern Michigan, Fr. Gabriel retained his love of teaching. Even before the War of 1812, he established schools, including Spring Hill School where Indian children learned with white children. He also sent a nun and teacher, Elizabeth Lyons, to New York to learn how to educate the deaf mutes of Detroit. His greatest academic achievements, however, began in 1817, when he and other leaders in Michigan, discussed a plan to build a territorial university. The Catholepistemaid, or University of Michigan, was born, and on September 24, 1817 the cornerstone was laid. Fr. Gabriel then moved on to drafting an order to create an elementary school system and a classical academy.

In 1823, Fr. Gabriel officially stepped into politics, running as Michigan’s congressional delegate at the encouragement of French-speaking citizens in the state. He saw it as an opportunity to press his plans for better educational facilities and missions for the Indians. Many claimed he had no business in politics and his opponents in the race attacked his credibility reminding all about the fact that Fr. Gabriel was still not an American citizen and thus, ineligible to run. Many of his opponents disapproved of him because of his Catholic faith and the fact that he was a Frenchman. In response, Fr. Gabriel applied for citizenship and was granted it on June 28, 1823. Many French-Americans rallied behind Fr. Gabriel and he was elected and took his seat on December 8.

In Congress, Fr. Gabriel was met with resistance and prejudice, but he worked hard, and attempted to push legislation to aid the deaf. Unfortunately, the bill he introduced died. He also promoted Federal road-building in Michigan and the bill he introduced to accomplish this did pass on March 3, 1825.When the time came for Fr. Gabriel’s reelection, his opponents again did everything they could to defeat him. They moved the date of the election up to a time where most French trappers, men who would vote for Fr. Gabriel, were in the woods. They denied Fr. Gabriel’s supporters ballots because they failed to pay a head tax, although men who did not support Fr. Gabriel and had not paid the same tax were allowed to vote. Some of Fr. Gabriel’s supporters were forcibly prevented from voting and ballots that had been misplaced in an incorrect ballot box were not counted, although those for his opponents were. The election results were close, but Fr. Gabriel lost. Though he protested, the Congressional committee investigating the matter found no fraud.

From 1825 to 1832, Fr. Gabriel continued to work for the people of his diocese. In early July, a cholera epidemic invaded Detroit, brought by American soldiers moving west. Civilians who were able to help those who had been struck down with the disease did so. Fr. Gabriel worked tirelessly to tend the sick, but at the age of 65, he was already physically weary and in poor health. He contracted cholera, and though many cared for him and prayed for his recovery, he passed away on Thursday, September 13, 1832.

Fr. Gabriel Richard attempted and accomplish many of his goals, including those that played a pivotal role in forming the city of Detroit. He set such an example of living a caring and giving life that even many non-Catholics looked to him with esteem. An exceptional man with exceptional accomplishments Fr. Gabriel will always be remembered as a great man who did much for all the people of Michigan.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.